In Photos: Jewish Africa

Jono David’s ‘never-ending Jewish photo tour’ led him to document a diverse collection of the African continent’s often-overlooked Jewish communities, both new and old

In July 1997, I embarked upon a six-week rail odyssey from Beijing, China to London, England.

The journey was the realization of a long-held dream. Its promise was greater than I could have imagined.

Sojourns in bucolic Mongolia and at Lake Baikal, the world’s deepest and largest freshwater lake, in Siberia, did not disappoint. Down the line, I would alight in Moscow, St. Petersburg, each of the Baltic states, and Warsaw, before pulling into London’s Waterloo Station, spitting distance from the shabby digs I once called home.

But something unforeseen happened on that great adventure.

Unexpected change of course

In Irkutsk, I stopped into the synagogue and was warmly welcomed by a few locals and an American visitor who was residing there temporarily for a research project. The encounter unwittingly set in motion an entirely different thought approach to the journey.

While I was wholly engrossed in everything the train journey in itself had to offer, I became equally focused on my Russian Jewish roots on my father’s side. When I reached Poland, I wondered about my Polish Jewish heritage on my mother’s side and, more specifically, where my great-grandmother’s hometown may be. I knew her — and her latkes — well. She passed away when I was 18.

By the time I got home to Osaka, Japan (where I had been living since 1994) that September, my mind was already made up: I was going to go back to Central Europe in February-March with the sole intent of taking as many “Jewish photographs” as possible.

My first “official” Jewish photo tour

I flew to Frankfurt, then took a train to Prague. From there, the haphazard journey took me to several corners of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland and Austria.

It was utterly unorganized. No appointments. No advance permissions. No schedules. No benefit of the internet. And poor photo skills.

I could not have known it at the time, but the trip was my first “official” Jewish photo tour. It sparked a lifelong commitment to documenting the Jewish world in photographs.

Over the years and many trips of a lifetime later, I realized it was time for something bigger, better, bolder. In 2010, I turned my sights to Jewish Africa. While I had previously visited some parts of northern Africa and traversed southern Africa, those trips — like the Trans-Siberian Railway — were primarily for tourism peppered with a few Jewish photo ops. In other words, they were not Jewish photo tours per se, and they were certainly not structured.

I had merely amassed a collection of images. But Jewish Africa was going to be different.

Developing African Jewish communities

Between August 2012 and April 2016, I embarked upon eight unique Jewish Africa photo tours comprised of some 60 total weeks of travel to 30 countries and territories. Ultimately, I archived some 65,000 Jewish Africa photographs, and I did so with the aim of answering one primary question: Who are the Jews of Africa?

I was particularly interested in the emerging Black Jewish communities in places such as Uganda, Kenya, Ghana, Madagascar, Gabon, and Cameroon. Over the last 20 or so years, the phenomenon of religious renouncement and self-conversion to Judaism has – in some cases, such as in Ghana, Cameroon, and Gabon – grown with the rise of internet connections there: Real-time connections are weaving a Black Jewish tapestry across the continent.

So far, these small but fervent communities remain largely ignored by official entities in Israel and in the mainstream Jewish world — the century-old Abayudaya community in Uganda is officially recognized by Conservative Judaism, but that is an exception.

Connections with outside Jewish organizations and rabbis are increasing, however, and official Jewish recognition remains an important aim.

European roots across the continent

In my travels, these communities held a particular fascination, but I was equally mindful of the European-rooted congregations. I was curious not merely about their history, but about their manifestations of Jewish life in comparison to the familiar ways in Europe.

The community in South Africa, for instance, began mainly under British rule in the 19th century. They are predominantly Ashkenazi Jews descended from pre- and post-Holocaust immigrant Lithuanian Jews. Between about 1880 and 1940, the community had swelled to some 40,000 (it peaked at about 120,000 in the 1970s).

It may even be said that a Jewish influence in the region dates back to the 1400s and Portuguese exploration with Jewish cartographers who assisted explorers Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama. But it was not until the 1820s that Jews had any significant presence. In 1841, they built their first synagogue in Cape Town. In the 1880s, a gold rush lured thousands more Jews, mainly from Lithuania.

Over the years, Jews all across the southern African region have had a disproportionately large influence on local society, politics, business, and history. In fact, the same may be said of Jewish settlements from Kenya to northern African nations too.

Jewish colonies in what are today Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Zambia, and Namibia all thrived. They built their synagogues, schools, and social centers very much in European architectural styles — with some notable exceptions in South Africa, which feature Cape Dutch designs and in the Maghreb, which feature Islamic and Moorish lines — and maintained all the trappings, traditions, customs, and culinary flavors from their homelands. I found these consistencies compelling evidence of the ties that bind Jews the world over.

Despite their successes in these far-flung lands, there were hardships aplenty. Early settlers in the southern African region forged across dry and dusty lands to create new settlements. Some sought riches in diamonds, sealing and whaling, and ostrich farming. Others, meanwhile, went on to prominent political and judicial posts. Yet, anti-Semitism had not been entirely left behind in Europe.

Though freedom of worship was granted to all South African residents in 1870, an 1894 law, for instance, debarred Jews from military posts and various political positions. In 1937, the Aliens Act aimed to stem the flow of Jewish refugees coming from Germany. Jews also faced resistance from pro-German Afrikaners. And they waded through the emotional and moral minefield that was apartheid.

Today, while Jewish communities of the southern African region shrink and ancient ones of the Maghreb cling on (notably in Morocco and Tunisia), Black Jewish groups are growing in number, in location, in commitment. Following subjugation over the centuries by both political and religious invaders, motivating factors for this Jewish awakening are rooted in a quest for truth and identity: a truth rooted in the tenants of Judaism and the Torah, an identity founded in self-determination.

My photographs endeavor to weave together this complex tapestry of the Jewish African peoples segregated by historical, cultural, linguistic, and regional divides yet united by a faith in Hashem.

—

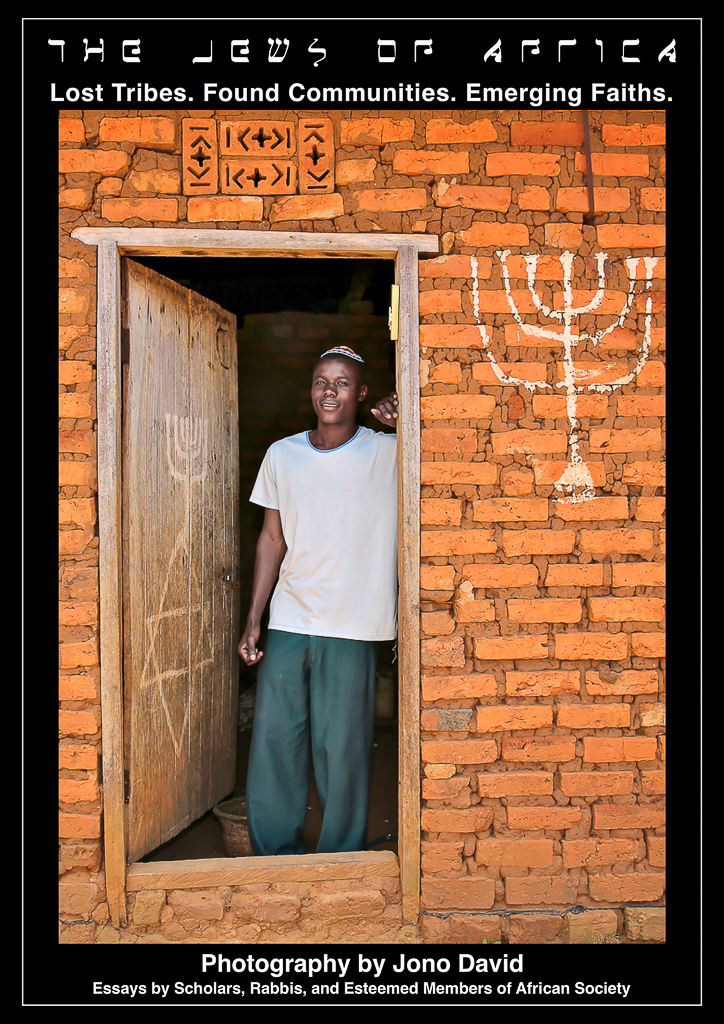

Since the late 1990s, British-born photographer Jono David has traveled the globe, amassing an extensive archive of contemporary images of Jewish heritage and heritage sites in the world – a growing compendium of more than 120,000 photographs from 116 countries and territories. His recent book, The Jews of Africa: Lost Tribes, Found Communities, Emerging Faiths, is based on years of travel to some 30 African countries and territories. It includes 230 photographs and 14 essays by scholars, rabbis, and members of Jewish African society.